Summary: Passwords are one of the most vital aspects to our online security, and one of the most infuriating. There are many ways to solve the issue, here is just one.

Solving the password issue...at least one way to do so...

BLOT: (21 Oct 2012 - 03:20:43 PM)

Solving the password issue...at least one way to do so...

Passwords are a paradox.

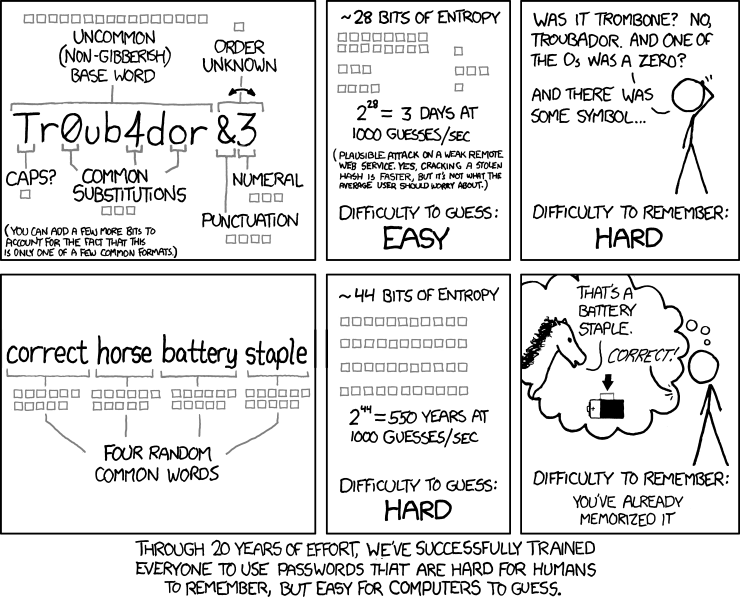

The longer they are, and the more complex, the safer they are...and also the more likely you are to use the same password across many different websites and the more likely you are to write it down or to have to use "Forgot-My-Password" style links. The more unique they are (per website), the better...except they are probably shorter and...well, you get where it is going. A perfect password is only used for one account, is fair-sized in length, suitably complex as not to be readily guessed (see:

This has lead to some bizarre choices from the sort of sysadmins who are responsible for protecting your online security: requiring passwords with highly specific (and technically limiting) requirements, expiring passwords at specific times while requiring entirely new passwords to replace them, and generally a host of other decisions that foster password-anxiety, lead to shortcuts and bad habits, and increase the likelihood that people will use lots of passwords generated on the fly and protected by the sort of security questions that a Facebook profile can answer (assume they actually answer the questions honestly). See, this XKCD comic...

Part of the problem is that we still live under the false assumption that password thieves sit down at terminals and flail on the keyboard to guess at our password using things they find around our desk (assuming, you know, you don't just tape your password to your desktop at work, in which case it might be true). The real ways that passwords are compromised look something like this:

- Keylogging malware tracks when you enter a password and transmits it back to a central server.

- Servers are cracked and password logs are accessed. Sometimes these are simply stored in the clear...

- ...and when they are not stored in the clear, brute force attacks on the hash against a dictionary file mean they don't have to crack your password so much as confirm its hash against another's.

- Passwords transmitted over a network (especially an open one, like you might have at a place that brags about it's free wi-fi) can sometimes be caught by a packet sniffer.

- Hackers get control of an email address and use it to activate lots of "forgot-the-password" links.

- After confirming your password on one website, they can use it to test on other websites. And/or the use the data on that site to pretend to be you and/or to send out highly tailored spam that looks legit to phish you for more passwords. And/or use the data to guess your "secret questions".

- Physical documents with passwords are sometimes compromised [if you do feel like throwing out lists of passwords, be sure to toss in some FUD or, I don't know, maybe shred the bastard...]

- And if you trusted a friend with a password, assume they have written it down in a public place before typing it into a machine with a keylogger exploit and that they sent it in the clear over a dozen open networks...

While making passwords longer and stronger (*giggle*) helps by making a password trickier to associate with a hash (no one is going to brute-force all potential 20-character combinations, since trying to store that much data would take billions of billions of billions of etc bytes and many many hours and while that is possible, too many low-hanging fruits to make it, for now, unnecessary), it is not a perfect solution. The blog entry "Long Passwords are Strong Passwords" has some great tips for turning a phrase like "Bronco's going shopping" or "taxes-for-Ponies.gov" into long, strong-ish, memorable passwords. But, really, if you have to create a unique password for twenty websites and use them for a not terribly long period of time, even remembering phrases like "$3 for the pirate hat" becomes non-trivial.

Ultimately, passwords that are longish and strongish but fleeting and not greatly repeated avoid many of the major flaws. Even if a keylogger builds up a list of your used passwords, if the list is ever-changing it is harder to be used against you later. By the time your hash has been solved, that password is moved along. But you probably see the problem, here. The human brain is not going to be able to whip out a constant stream of these things across many accounts with each changed out every few months. Eventually the phrases are going to criss-cross in the brain and the "forgot-your-password" button is going to get used all the same.

What's the solution? Well, one perfectly viable solution is to use something like LastPass (see the LastPass Wikipedia entry for some more info). The guy who wrote the "long is strong" article above, Mark Burnett, has even recommended this in his article "My Advice, Just Use a Password Manager". I have not used it, but presumably the passwords can be set to change often and with various strengths. Of course, there are ways that such things can be cracked and it is not too huge a stretch to imagine someone's entire password collection being pilfered by no fault of your own as a third party drops the ball. At least you should be able to rapidly update your passwords [including your LastPass one] so that if it did happen, maybe by the time they take advantage of it, it will be too late to do harm].

Another is to take something that makes quite varied passwords but is systematic enough that you could rebuild passwords on the fly only knowing a few details that can be cycled in and out so that you never remember a password, you remember how you made a password with enough options to at least slow down the buggers trying to rip you off. There is an old trick where you take, say, three parts. The first part is a root word, and it can be a word or anything you remember. Then you take another part, which might be another word, but this one is specific to the domain [e.g., for Twitter.com you might use, simply "Twitter.com" and you might use "tweetplace" or "microblog"]. Finally, you take a third one, that might be based on the user name [but, obviously, shouldn't be the username]. Or maybe it is based on use of the account (commercial use, social site, etc). Then, to make your password, you combine these three things and assuming that the each part is 5-8 characters, you can create a 15-24 character password. Then, about once a season you switch out the first part and about once a year you switch the last part. Each site gets a unique second part so that you get to remember your passwords for those sites just by stapling the two together, and the third part allows you to use different passwords for different accounts. And you can change the order up every other season, as well. Not perfect, especially if someone is particularly trying to crack into your stuff and knows the system and figures out the parts, but it allows for longer passwords that can be changed fairly regularly.

I decided to take the concept of algorithmic passwords one step further. To take a root word that uses the user name and the domain to cipher out a certain number of characters (let's say 8 to 10) and then staples this to a prefix and a suffix (another 8-10 characters, maybe more), and then allow various ways for extra chaos to be added to the seed. The ciphering table is mutable so that it can be altered over time, if needed. And there are many tricks to change out stuff, but the trick is, hopefully, to keep these tricks more personally retainable than many long, complex passwords. The link, right there, is my starting steps on this. I will continue to expand it some as I go.

This still has the issue that you have to access to the algorithm, which in this case is access to that page (though feel free to tweak out your own from it). And it is not simple, if you are on a mobile device, to whip that out (*giggle*) and plug in all the necessary details, especially if you have a fairly randomish character set [and, outside of a complicated seeding mechanism, the randomish character set is the best bit to slow people down]. Since you are using an algorithm, if several parts become known the last couple of parts might be solvable, so changing out and varying the parts is required. But, overall, this works for me. I know I am different than others but I'm happy with how round one turned out. Though changing all the passwords? That takes frickin' forever. Luckily, once I finish the process once, I'll have a sheet of passwords that I can mark as "change" or "no change" and then managing them will get easier.

Since I have a couple of articles by Burnett linked, I figure I should include a couple of other ones for the funsies [well, one for funsies and one for the source of the data used in the word cloud, above]. The first one is decent advice, the second let's you know what I meant by the "low-hanging fruit" line, above.

OTHER BLOTS THIS MONTH: October 2012

dickens of a blog

Written by Doug Bolden

For those wishing to get in touch, you can contact me in a number of ways

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The longer, fuller version of this text can be found on my FAQ: "Can I Use Something I Found on the Site?".

"The hidden is greater than the seen."