Library of America releases Lynd Ward's Six [wordless] Novels in Woodcuts. Worth checking out...

BLOT: (17 Oct 2010 - 10:18:41 AM)

Library of America releases Lynd Ward's Six [wordless] Novels in Woodcuts. Worth checking out...

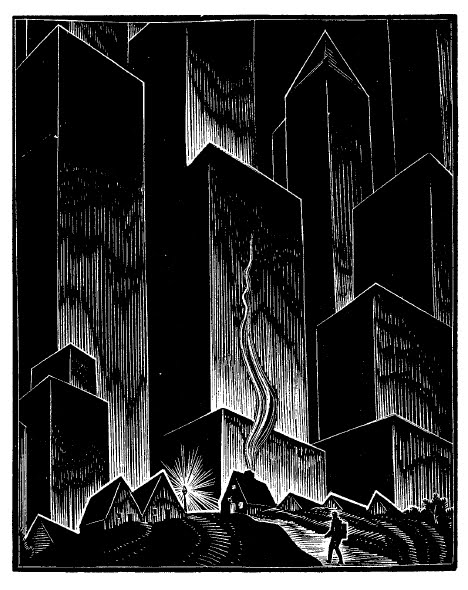

It is weird to think of books with no words as being literary, but the wordless novels of Lynd Ward count. There are plotted out, show structural themes and twists, have character development and pathos. The story is accomplished through black and white woodcuts [ink stamped by carved wood, allowing for single-tone images but often involving a number of shading techniques, see Wikipedia for more], with elements ranging from surreal scenes heavily influenced by silent films (see graphic below for a

Just to highlight the capabilities of the wordless novel, we'll take a quick look at

Ward is not trying to dig deep with this one. He was the son of a Methodist pastor and he went on to help several Methodist influenced political causes around the time of the Great Depression. He paints the story of a country innocent, not so much caught up in the debauchery of the city—or should I say, The City?— but mostly unable to realize what the debauchery of the city is until it is too late. He flees in the end, but he brings death with him. It is the inherent goodness of man hiding out under the sin, but only surfacing after depravity is reached. Modern readers might balk at the solution to all the man's problems being to find a quiet, blonde wife in the country-side. At least the ending brings the novel's only complex plot point: we can overcome our personal evils, but there is still a price to pay. Ward's artwork is the highlight throughout, some scenes being filled up wit imagery and concepts, and onthers focusing on only a couple. He is not in the same vein as some of the woodcuts most often displayed in textbooks and such, he opts for something simpler and more stark—more Frans Masereel than Gustave Doré—but there is still plenty of food for the eyes. A few pages fall into the narrative cracks, not quite making sense in the overall arch of thing, but the majority are more than functional. He takes a story that would have been a trite novella if written in words, and make it much more beautiful without them.

In something like a bonus, I came across this page on Lynn [sic] Ward from Texas Chapbook Press. Despite the name being wrong, it gets the number of wordless novels wrong, and claims the allegorical

TAGs: Books

BY WEEK: 2010, Week 41

BY MONTH: October 2010

dickens of a blog

Written by Doug Bolden

For those wishing to get in touch, you can contact me in a number of ways

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

The longer, fuller version of this text can be found on my FAQ: "Can I Use Something I Found on the Site?".

"The hidden is greater than the seen."